International Women in Engineering Day, a day dedicated to the amplification of women in the industry, began with the formation of the Women’s Engineering Society in 1919 by a group of trailblazing women who embraced roles in engineering during the First World War and were determined to continue their careers in the field.

While there are countless brilliant female engineers like Marita Cheng, Dr. Morley Muse, and Dr. Mehreen Faruqi, with phenomenal contributions to the field, I would like to draw your attention to the reasons many more visionary female engineers have chosen to leave the profession and what we need to do as a collective to shift this trend.

The attrition rate

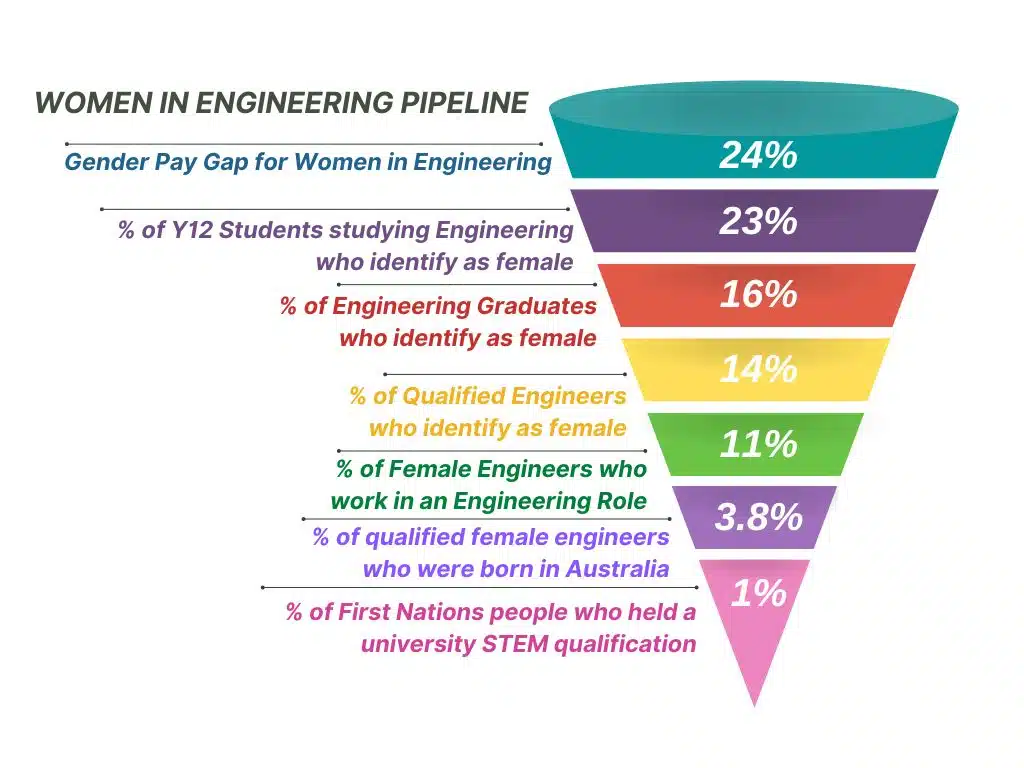

The pipeline in the image below paints a disparaging picture of the attrition rate of engineering students who identify as female from Year 12 to those who qualify and work in an engineering role, a mere 11%, only 3.8% of which were born in Australia. We know that the attrition does not stop there. The percentage of women who continue to progress to senior engineering roles is even less.

While 23% of Year 12 students studying engineering identify as female, they make up only 16% of graduates, 14% of those qualified, and 11% of those working in an engineering role (graphic provided by author).

Adding on to this, the gender pay gap for women in engineering as recorded by Professionals Australia in 2023 remained high at 24% in comparison to the average across all industries, 14.1%.

Why aren’t high-paying roles in an ever-growing digital economy attracting interest from female tech enthusiasts? The answer has always been a dark and sinister one, safety – physical, psychological, and emotional safety. Women cannot and will not take up studies, degrees, and roles that have generationally been known as unsafe environments for women. The pipeline above is proof that even when female students do choose to study the field, it is unlikely that they will continue to graduate with an engineering degree and work in the field.

The myth of physical strength

Studies continue to show that women are less likely to be pursue engineering occupations such as electrical, mechanical, or civil engineering that require presence on the factory floor or on site. Attracting interest from female students to engineering occupations that require physical presence on the factory floor or on-site will require more than an advertisement featuring a female engineer with a hard-hat and a high visibility vest. Corrective measures include:

- Employers need to proactively counter the stereotype that a “built male” is likely to be hired, promoted, and renumerated.

- All machinery, equipment and tools procured need to be fit for operation by women without needing to apply excessive physical force.

- Ensure that female engineers are meaningfully included in the design of machinery and equipment to ensure that safety and operational perspectives from a gendered lens are included in design specifications.

On-site safety

Construction sites and factory floors aren’t exactly welcoming to female engineers, particularly if you’re one amongst 15 other male colleagues. It takes commitment from employers to ensure that factory environments and sites are visibly safe for women. The lived-experience and expertise of female-engineers who work on site need to be centered in the design of the safety features of on-site locations.

This could include the following:

- Ensuring that sites are visibly well lit, surveilled, and attendance is logged.

- Ensure that Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is fit-for-size as ill-fitting PPE can be incredibly dangerous in high-risk conditions.

- Ensure preventative sexual harassment processes and policies are firmly in place

- Anti-bias reporting and accountability procedures

Visible safety is paramount to improve female participation in on-site jobs. Let us not undermine the ever-present threat of gendered violence in sites that can have an overrepresentation of male workers. Employers have a positive duty to ensure that proactive and visible preventative safety measures against gendered violence are present on-site.

Anti-harassment and bullying

The Women in Engineering report by Engineers Australia in 2022 states that the primary driver of women leaving the engineering workforce is bullying or exclusion of women in the workplace. 1 in 5 women reported experiencing bullying or exclusion in the workplace. While many female engineers like me have experienced exclusion within the organisation, primary forms of bullying can be perpetrated by external parties such as contractors, vendors, tradespeople, and clients.

Employers seeking to improve female representation in engineering roles will need to do more than promote a zero-tolerance policy against bullying and harassment. Corrective measures include:

- Psychologically safe forms of whistleblowing and reporting need to be available and represented by a critical mass of female engineers.

- Female Engineers need to be able to impose a “Stop Now” policy with any vendor, contractor, or client that does not adhere to safety policies.

- Anti-bias training, policies, and reporting need to be in place to prevent occurrences of microaggressions against female engineers.

- Organisations need to proactively counter the narrative that female engineers will be shunted to administration or managerial roles and instead promote adequate representation of female engineers in technical roles.

Centring the voices of female engineers in product and site design

Sustainable and effective change to workplace culture can only occur when the voices of female engineers with lived experience are centered as demonstrated in DCA’s Centring Marginalised Voices at Work Report (2024). Women cannot be expected to participate in an industry that designs clothing, tools, equipment, machinery, and worksites for men. Women need to be involved in the diagnosis of issues in all areas and part of the co-design process to ensure that all design specifications include perspectives from a gendered lens.

Women then need to be part of the co-create and co-evaluate process to ensure that any technical product or site is fit for purpose and well and truly includes the needs of female engineers, female clients, and female end-users. This will not only open the industry to a new range of female clientele but prevent issues like airbags and collision avoidance mechanisms that aren’t effective for women because crash test dummies were designed based on the male physique.

It just makes sense

We shouldn’t have to request separate toilet facilities, fit-for-size PPE, and protection against gender and sexual violence at work but here we are. Sustainable change in female representation cannot change without first ensuring that female engineers can operate tools, machinery, and equipment comfortably. The number of female engineers will continue to remain stagnant if female engineers continue to feel unsafe at work.

This International Women in Engineering Day, I call for the theme for this year “Enhanced Engineering” to ensure that the physical build and physical safety of female engineers is a required consideration in all technical solution and design.

Shalani Tharumanathan (she/her) is a qualified electronics engineer, a certified data center professional, and an experienced network solutions consultant. Her experience spans six years in the telecommunications industry and three years as a STEM VCE educator in lower socio-economic communities teaching Applied Computing and Engineering. Her lived experience as a female engineer from a culturally and racially marginalised (CARM) and lower-socioeconomic background informs her work in D&I. Shalani is also the project manager of the RISE Project at DCA.